What we can learn from the JP Morgan Traders.

Allegedly! It’s America after all, and we love that word.

But, it is the question that people keep asking. “What exactly did the JP Morgan precious metals traders actually do that got them into so much trouble?”

It’s a case study in spoofing. Here’s what you need to know.

A spoof is a market order that is placed with the intention of being canceled before execution. Memorize that. No matter how complex it always comes back to this: an order placed with the intention of being canceled before execution.

Here’s an example. A trading intern is sitting in front of an open trading screen. The trader stepped out for a break. One of her fellow interns dares her to enter an order, but then cancel it before anything happens. She thinks about it. Glances over her shoulder to see if anyone is paying attention. Musters up her courage and goes for it. From intern to inmate in a split second, she has just committed a crime.

- Is it because she did not have permission to trade under that user name? No!

- Is it because her order contributed to a disorderly market? No!

- Is it because she placed an order with the intent to cancel before execution? Yes!

When I said memorize that, I’m not kidding. Lock that into your forever memory. “Placed an order with the intent to cancel before execution.”

The Usual Spoof

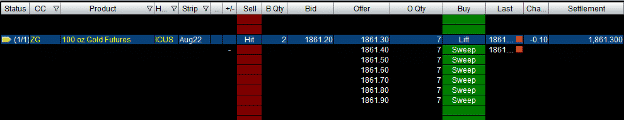

Look at this screen. What do you see?

There is a bid to buy (B Qty) of 2 lots at $1861.20 and an offer (O Qty) to sell 100 lots at $1861.90. What is this market saying to us? More gold for sale than there are buyers. More supply than demand. That’s bearish. All things being equal the price may go down. So, if you had gold to sell you might consider taking that buyer up on their 2 lot offer.

What you can’t see is that the buyer and the seller are the same trader. Nothing illegal about being on the bid and offer at the same time. That’s just making a market. But because it’s an anonymous book no one knows this is the same trader.

So what is the problem? Back to basics. The trader placed an order with the intent to cancel before execution. That 100 lot offer? It’s meant to be canceled. How do we know? Because when the 2 lot bid got hit, he canceled it. The 100 lot order was placed to “spoof” the market into thinking there was more supply than demand. The trader gets his bid hit and the 100 lot order gets canceled. That is your basic spoof. Every surveillance system is set up to alert on this.

On to JP Morgan

What the JP Morgan traders allegedly were doing was just a tad more sophisticated. Their screen looked more like this.

Instead of 100 lots, they would just layer a bunch of small orders. So it looks like there are a bunch of different sellers. In reality, this is a spoofing mechanism where all those 7 lot offers are the same trader. The JP Morgan surveillance system was never configured to capture the net effect of a lot of little lot orders. Only single bigger lot orders. They were trading in a way that let them get around alerting the compliance officers. And boy did they do a lot of it.

All the ‘buts’

“But the spoof order was exposed to market risk. A lot of market risk actually. It’s not certain that the trader could cancel. Someone might have lifted that offer.”

True. But back to basics. The trader placed an order with the intent to cancel before execution. In this case the trader put in all these little orders with the intent to cancel them before execution. They were trying to spoof the market into believing there were far more lots for sale than buyers. Getting filled on an order intended to be canceled? Irrelevant. It just makes proving the spoof harder. But it’s still a spoof.

“But the alleged spoofing did not even move the market really. We can’t see any effect this bidding behavior had on the market.”

Sure. That’s a great data point. But lets go back to basics. Did the trader still place an order with the intent to cancel? If the answer is yes then whether or not the trader was successful in their spoof or moved the market is irrelevant.

“But how do you prove what was in the trader’s head? How do you prove that they had the intent to cancel?”

This is tough for any lawyer. But you can imagine piles of direct and indirect evidence. The fact that the trader got his fill and then canceled the opposing order(s) is the death blow. As we are seeing in the JP Morgan trial there are also chats between traders. Repeatedly doing it again and again showing a course of intentional conduct that was profitable, and hence establishing a clear motive. All of these lead to the conclusion about what was inside the traders head when they placed these orders. They knew exactly what they were doing.

The take-aways

- We are amazed by the number of firms that don’t have a good handle on order data. Getting your traders market activity down to the button press is very simple. If your firm is trading and you need help getting your orders data give us a call.

- Traders and compliance officers need to pay especially close attention to trading behavior when making markets (where traders are on both sides of the market at or near the same time). Most traders are professionals and know to be careful, but it’s one of those areas that demands constant surveillance, reminders and attention by compliance and trading teams.

- That goes for cancellations as well. It’s easy to get complacent about just taking an order down. But think about it. The cancellation is the one thing that proves an order may have been placed with intent to cancel. Again most traders are professionals. But being incautious about order placement is very risky.

As always we’d love to hear what you think.. Drop us a line if you need direction to getting your order data intelligence set up. We are always happy to share what we know.